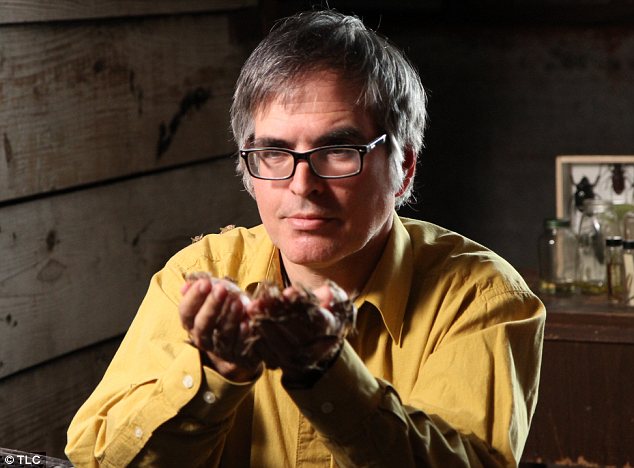

Interview with David Gracer, English teacher, writer and naturalist in Providence, RI. He teaches at the Community College of Rhode Island and has contributed to the Entomophagy movement

Interview with David Gracer, English teacher, writer and naturalist in Providence, RI. He teaches at the Community College of Rhode Island and has contributed to the Entomophagy movement

What amount of psychological work is needed to change our food habits?

This question and the next one present several problems. The field of entomophagy has seen recent and encouraging technological and entrepreneurial developments, but other aspects of the subject remain unexplored. It is very important that we acknowledge and discuss our own referential frames; this includes phrases such as our food habits, and the use of plural pronouns in general. Entomophagy is definitely a global subject, and it is unlikely that everyone who reads these interviews was born in or currently resides in a country or region commonly referred to as Western. My research includes material on insects, on human culture, and on attitudes regarding group-normative-behaviors. There is much more to say on these topics. Commercial and humanitarian agendas alike depend upon understanding people.

Many researchers have noted the intensity with which most people throughout the world prefer their inherited, group-normative food-sources. Although some observers of the entomophagy industry might posit that the expansion of commercial entomophagy indicates societal shift in favor of entomophagy, this progress exists within strict limits because the consumers represent very small percentages of the population. Technological and entrepreneurial progress does not necessarily lead to general acceptance. I have not seen commentary regarding criteria by which we could quantify the economic, humanitarian, and environmental potential of this industry; it would be wonderful to learn from sociologists, economists, and other researchers about these aspects.

Is western society psychologically ready to accept the idea of eating insects?

The phrase western society is highly problematic in current discourse regarding entomophagy. A thorough examination of entomophagy leads to issues of individual and group identity that resist simple explication, and are therefore rarely discussed in the journalistic coverage of entomophagy (he same may well be true of scientific investigations). Most public-media coverage includes only the standard talking points:

– the presence of edible insects in the diets of many human populations worldwide

– the nutritional attributes and physiological benefits of insect consumption

– the scientific findings of the FAO and/or other experts

– concern regarding the future sustainability of vertebrate-protein-production

– the general public’s standard negative reactions

I find the more philosophical implications of entomophagy to be very compelling, and of course these are implied in this question. Although some people might consider these possibly-existential aspects too esoteric, exploring them could help create real, measurable development of entomophagy, which has bearing upon the future of human civilization.

Positive and negative reactions to entomophagy are part of a much larger story, which involves history, anthropology, and other subjects within the Humanities. Globalization, and the Age of Colonialism that occurred before it, has caused massive disruption in a wide variety of human behaviors. In many cases, normative behaviors of European-based societies spread to other regions. This is an important factor in the substantial reduction of entomophagy from many so-called “non-western” regions. Generally speaking, the peoples of those regions tend to have well-documented traditions of insect consumption, yet the loss of this dietary habit is also well-documented over the past several decades. I coined a term –Acquired Food-Source Rejection, or AFSR– to document the cultural shifts that have caused people in many traditionally insect-consuming communities to dismiss entomophagy as a primitive behavior. This abandoning of traditions (whether entomophagy or some other cultural practice) is extremely important.

Similarly, discussing the “acceptance of entomophagy” invites us to establish criteria by which we could quantify the phenomenon. It is not sensible to claim that a given society accepts insects as food if only a small percentage of the population is actually doing so.

Is the “yuck factor” a mix of economical reasons (big animals as food were and are more widely available in the west) and psychological ones? Is there an economical factor in a food taboo, like associating bugs with crop pests?

The various negative reactions often described as yuck factor are an essential part of the future of entomophagy, and require a great deal of further study. The relatively recent development of “Disgust Studies” is useful in this regard. Disgust is an extremely complicated subject, and we can observe this phenomenon in the ways that entomophagy is represented in public media around the world. These difficulties of perspective [regarding whether insects are or are not an acceptable food-source] are likely to intensify if global conditions begin to visibly threaten the food-preferences of billions of people. Societal health depends upon the steady, affordable supply of desirable food-items, yet anthropogenic climate change is jeopardizing our collective future, even as population growth will require steep increases in protein production over the next several decades. All of this is part of the greater narrative of entomophagy, which connects humankind’s past, present, and future.

Although I have not thoroughly investigated the economic and logistical requirements of industrial-scale insect-production, it appears that our industry has not substantially reached parity regarding price-points for a given unit of processed final product, as compared to conventional protein-sources. This is one of the many difficult issues concerning entomophagy.

Can food styling help to decrease consumer disgust, and thereby play a crucial role in the insect-based foods acceptance?

Yes, utilizing food-preparation machinery to transform insect ingredients, and marketing products that incorporate insect flour, will probably make entomophagy somewhat more acceptable to the general public. However, advancements in the manipulation of insect ingredients should not cause us to ignore the typical, negative reactions to insects in general and entomophagy in particular. Claude Levi-Strauss observed that “the brain eats before the mouth”, indicating that the acceptability of a given food-source is ultimately a psychological matter. Therefore, enhancing culinary technique might not be the optimal method for encouraging the acceptance of foreign foods such as insects.

We can do much more to recognize and address the underlying reasons that cause most people in developed nations –and substantial percentages of people in many less-developed nations– to reject entomophagy. It is through education (concerning what insects are; how they enable the movement of energy in ecosystems; the harmlessness of the vast majority of insect species; and humankind’s dependence upon the activities of insects for pollination, waste disposal, etc.) that we have a chance to positively influence perceptions.

An old idiom states “you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear”. In the minds of the general public in thousands of cities worldwide, this sentiment applies to the manipulation of ingredients. Cynics are likely to view the manipulation of insect-based foods as typical, cosmetic marketing – or, far worse, as propagandistic attempts to indoctrinate the masses. Despite the success of entrepreneurs and others in recent years, I suspect that public revulsion and rejection of entomophagy is becoming stronger as the need for entomophagy has gradually become more evident. Considering this, we should create new opportunities that could transform our perceptions of insects, which is itself an essential indicator of our relationships to Nature. This is the function of education. Developing general entomology outreach could include insect-based cooking and/or baking competitions, and could transform our collective relationship to the natural world.

Do you agree with the hypothesis that a growing environmental consciousness will be the “psychological kickstarter” to include edible insects in our diets?

Concern for the environment is clearly a motivator for interest in entomophagy, and that’s great. Having said this, we must remember that the harmful effects of deforestation, mining, transportation, livestock-production, overfishing, etc., have continued to worsen despite the increasingly ominous findings from the scientific community for well over twenty years. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that environmental consciousness is not a dominant motivator of human behavior, except for a relatively small percentage of the public.

According to the great majority of scientists who have published on entomophagy, is very likely that many societies will need either insect-based proteins or some other alternative protein-source at some point in the next several decades, either for animal feed or for direct human consumption. Similarly, it is possible that insects will achieve general acceptance only when preferred food-sources are no longer available in sufficient supply and price-points.

How we will accept this remains to be seen, but it is apparent that some societies will have greater success than others in gaining public acceptance for insect-based foods. Several European countries have begun comprehensive programs designed to popularize entomophagy, and it is logical to presume that these initiatives could be very beneficial in the event of any lapses in the availability of standard vertebrate-animal-proteins in the marketplace. The corollary is also true: societies that comprehensively dismiss entomophagy and other alternative food-sources will not benefit by their biases if interruptions in the delivery of desirable food-items occur.

Would showing images of insects help create appeal for insects as food? Or would it be better to hide the animal and just work on concepts?

Although I have not studied the intersection of psychology and marketing, and therefore do not have the expertise to answer this, I suspect that utilizing images of actual insects would be counter-productive. In mainstream American society, for example, it is common to transform animal-proteins from their original appearance (turning a chicken carcass into processed “chicken nuggets”, and cow flesh into processed hamburgers, etc.). Therefore it is reasonable to conclude that it would be helpful to alter the physical appearance of insects and that to market that final products without direct images of insects.

It is fascinating to consider the great variety of logos and other icons already used among the companies and other organizations already working in the field of edible insects.

What’s the role of stories, novels, movies and cartoons in “creating monsters”?

There is little question that the majority of media representations of insects in general and entomophagy in particular tend to emphasize the negative perception of our subject, and therefore might be considered harmful. Even though these depictions often condemn or mock the concept of insect consumption, and may bias some people even further from considering insects as a food-source, I feel that all media coverage of our subject is beneficial. If we wish to expand entomophagy, we must continue to address the public with many varieties of discourse and to “meet them in the middle”. Media that dismisses entomophagy, or that posits insect-consumption as an unpleasant ordeal (a standard trope in reality television shows) is still superior to no media coverage at all, because it can initiate conversations among viewers. This is why I have regularly engaged in so-called “lowbrow” discourse on entomophagy, such as reality television shows, as well as more high-minded efforts like academic conferences.

What’s the worst comment about the idea of eating insects you’ve heard from a student?

I have included an entomophagy experience in my college-level writing courses for more than a decade, because the subject is a perfect avenue for developing critical-thinking-skills. I’ve also served insects to the public hundreds of times. Although some students and others have expressed a variety of negative comments, I have found that people in educational settings and at public events tend to be more receptive to new ideas, or are more likely to remain polite as they decline to sample the food.

By contrast, people who contribute comments to online media articles generally do so anonymously, and therefore are far likelier to express themselves scornfully, sometimes including harsh, class-related perspectives and even racist ideologies. Earlier I had mentioned “issues of individual and group identity,” and the commentary sections I have collected demonstrate the disgust, ignorance, and rage of certain sectors of the general public in the U.S. and in other countries.

At TEDx Cambridge in May 2010, a woman approached me during the reception. “I almost cried during your talk” she said “Based on your argument, I can definitely see that insects will be a big part of our future food supply. I thought about my daughter or my grandkids having to live like that!” Apparently she viewed the concept of entomophagy as a form of degradation and defeat. I offered regrets for having upset her, yet once again there are larger ideas at play.